Beautiful Brighton

Brighton isn't a diving region that I'm familiar with.

It's a bit of a drive from Somerset and the currents and visibility can be even worse than the more westerly reaches of the English Channel.

I knew there was good diving to be had there, I had just never felt motivated to visit.

All that changed when Ghost Fishing UK received dozens of reports from keen and active divers in the region. Furthermore, we were approached by Sussex Wildlife Trust to partake in their 'Wild Coat Sussex' project which centred around Brighton.

Ghost Fishing UK ran several missions over the summer surveying and recovering mostly lost nets but also plenty of lost crab pots as well. Immensely supportive of the project was Steve Johnson of Channel Diver. Before the team had even arrived, he'd made up some banners for his boat in support of Ghost Fishing UK and Sussex Wildlife Trust. We were truly humbled.

It is so important to support the diving industry who we rely on to keep divers diving and reporting this lost ghost gear.

To date, Ghost Fishing UK has chartered 26 different dive boats around the UK across 142 survey, recovery and training dives.

Even more exciting was that a local fishing trawler heard we were in the area and offered to come and help pull in the lost gear, something we were extremely grateful for.

Ghost Fishing UK has always wanted to work WITH the fishermen on the issue of lost gear. We have never believed that they want to lose it and therefore, pointing the finger of blame in their direction is, well, pointless.

I was on camera duty again and thoroughly enjoyed getting some underwater images of the action. It was a pleasure to dive with Kerry and James as they set about cutting up and removing some nasty, snaggy nets on a wreck in about 20 metres of water.

It was a long day and as I drove up to Aberdeen the very next day for work, I parked up in my van and sat up until midnight bashing out a press release for the next morning. It was time and effort well spent as almost every news outlet in the South East picked it up and we were invited for further interviews, news pieces and every journalist in Brighton wanted to come out on the boat with us!

It was great to get out of the admin/trustee/dogsbody chair and get into the water with my camera, doing what I love.

“Just like a parrot”

Osama and Christine set off into sump 2.

Oz and I quietly trudged up and down the passage between sump 2 and sump 3.

It was mostly walking, with an awkward boulder choke soon after sump 2.

There was a convenient hole to pass through but it was better not to touch anything above you and not look up. The sizeable hanging death was best out of sight and out of mind. We hadn’t managed to find a suitable way around it.

Christine carries her rebreather from sump 2 to sump 3.

Mauro didn’t get the memo and I bumped into him just after he’d passed through the boulder choke stating; “f****ck man if that stuff decided to come down now…..” .

He shuddered and carried on moving our bailout bottles.

Rich and Mauro saw us off into sump 3 which is a short and pleasant dive, before surfacing in the extremely irritating bit of passage before sump 4.

Only 8 metres long, this passage is extremely sharp and the entrance and exit at sump 4 has a needle-like layer of rock, perfect for tearing drysuits, stabbing knees despite knee pads and ripping hoses. This slab of rock on the entry to sump 4 (best done by giant stride in, levitation out…) was responsible for ripping Anton’s hose off his bailout in 2021.

Oz and I got away relatively lightly. His oxygen regulator unraveled itself in the pool, so we had an odd 5 minutes with me trying to fix it while Oz circumnavigated the pool doing doggy paddle. “Stay still for god’s sake!” was the best advice I could offer.

Reg fixed, I unclipped my mask from the safe place I had put it on the washing line, immediately dropping it into the sump that eats gear. Oz went down to rescue it, recovering the line reel I had dropped in the very same spot last year, at the same time….

Sump 4 goes on a bit, for several hundred metres and touches 30m depth at one point. It has an annoying vertical ascent with hardly any belays about 2/3 of the way through, then takes off again at 11m depth. I came across my tie off from 2021 and the line was still in good order for the final ascent.

The passage between sumps 4 and 5 was just as nice as I remembered it but of course, shorter.

Sump 5 was waiting, right where I left it.

Oz and I became a bit more chatty now that we had made it to the start of exploration. It was something of a relief to tie the line reel off and set off underwater into virgin territory.

I was hungry. The cold water and significant exertion of caving with a rebreather (forgetting we’d just done a 50m deep, 600m long tech dive…) meant hunger and thirst were real issues.

I ignored it and set off laying line into sump 5. The visibility started out murky from where we had trodden up the gravel while kitting up. It soon went instantly clear and in typical Licanke fashion, did not offer up any suitable belays in any suitable places.

I ran the line reel down to about 15m depth and marveled at the big, blue expanse ahead of me. The cave looked to be going ahead and off to my right, but it soon closed down. Scratching my head, I heard Oz calling for me (he was a little way behind, sorting the Mnemo surveying device). Divers can talk quite well on rebreathers, so I tied off my reel and swam back to see what the problem was.

Christine laying line into the brand new sump 5.

Oz was surprised to see me but swore he hadn’t called out for me. Clear as day I’d heard someone shout my name. Freaky.

I shrugged and went back to my line reel, casting around for ongoing passage. Half of me hoped for a continuation but the other half prayed that this would be the end of the cave and we could stop this 7-year nonsense and go home, carrying on with our lives, having fun elsewhere.

I had tipped literally thousands of pounds into this project, as had my team, and we did start to wonder just how much more we could take.

Oz caught up with me and pointed upwards.

Oh no.

Going up on rebreathers while laying line is stressful and it didn’t help that I was low on oxygen. I had a spare bottle back at sump 2 but I had to get back there first. All these ups and downs burn through oxygen on rebreathers and I wasn’t up for another ascent, which might be futile in any case. I started up the smooth wall and with only 50 bar of oxygen left, thought ‘stuff this’ and came back down, giving the line reel to Oz.

I picked up his Mnemo on the way back and started moving my bottles and rebreather back to sump 4, getting some of the work done for when Oz returned. At least I’d managed to film the dive on my Paralenz dive camera.

Another half an hour or so later he surfaced. The cave had continued very shallow, at about 2m with the occasional air bell. This is a nightmare on a rebreather so I had no regrets about not continuing.

Meanwhile, back between sump 2 and sump 3, Rich, a self-proclaimed introvert was spending hours at the mercy of an extremely excitable and talkative Italian.

He had worked out though that if you turned the helmet lights off, Mauro went silent.

Rich quickly exploited this tactic of ‘saving batteries’ by turning the lights off to get some peace and quiet. Explaining to us later he said he was a bit like a parrot – they go quiet when you throw a blanket over their cage!

To keep themselves occupied, I’d requested that they get some nice images and video from the decorated side passage in between sumps 2 and 3.

Of course, with no check list and the Italian method of ‘winging it’ the go pro didn’t make it through sump 2.

So, the guys had nothing to do the entire time we were gone.

Check lists. They are the future.

Christine has help kitting up from Mitch in sump 2.

During one of these pitch black siestas, Rich and Mauro both jumped up and turned their lights on as they both heard Oz and I returning. They made their way to sump 3 to greet us, only to be faced with nothing. There was nobody there...

They looked at each other, confused and slightly rattled...and spent another couple of awkward hours waiting for us.

Back at sump 5, Oz and I were making our way back home. I was now very hungry and feeling energy sapped. Food was available at sump 2, but we hadn’t brought any further in. Oz donated one of his baby food gel energy pouch things. It was utterly revolting but it gave me a short boost to get me back through to sump 2.

Rich went and got me some food when he realised his life was possibly in danger due to my hunger and I soon got ‘back in the room’ having eaten a tuna pasta tin of cat food.

Nutrition. We put that on the list for next time….

Due to excellent planning and timing, shortly after surfacing from Sump 2, the four of us could hear voices. The support team of Mark, Lou, Luke and Mitch had arrived and we were extremely grateful to see them.

We had been underground about 15 hours and discovered a couple of hundred metres of new underwater passage, which was still going. In addition, we completed the dry survey between sumps 4 and 5 and the remainder of sump 4. We left forward pushing bailout bottles at sump 5 as well.

We even got some video. That was a seriously productive day out.

Chris and Rich beyond sump 1. Image: Mark Burkey

This expedition has received generous assistance from several organisations and businesses listed below. We are grateful to our Croatian friends for their help and support over the last 7 years.

Izvor Licanke Expedition Team 2022: Mark Burkey, Louise McMahon, Luke Brock, Mitchell Parry, Richard Walker

Push divers: Christine Grosart, Osama Gobara, Mauro Bordignon.

The expedition reports, funded by Mount Everest Foundation, are available to read here:

Funding and support:

Santi Drysuits, Halcyon Dive Systems, Mount Everest Foundation, Ghar Parau Foundation,

The Crazy Claymore

“Claymore. I’ve heard of that...” I thought, looking at my email.

My first trip back to work after the dizzy success of Licanke, was to a big and well known North Sea asset, the Claymore Alpha.

Claymore was involved in the demise of the ill-fated Piper Alpha and continued to pump oil to the stricken platform while she burned.

A helicopter lands on the Claymore Alpha. Image taken from Boka Atlantis, by Christine Grosart

A dark history, but it fascinated me nonetheless and I was slightly perturbed by the comments I received from several people about heading out to the platform.

“Claymore? Oohh, you don’t want to go there....”

“Off to Claymore are you? Oh, right...”

Lots of teeth-sucking seemed to be triggered by the word ‘Claymore’ and I wondered exactly which pack of wolves I was about to be fed to.

I landed on the helideck and was given a long and very safety orientated induction.

Martyn, the existing medic was remaining on board while he learned the ropes for the HSE role on another Repsol asset. This was convenient, as it was considered you needed 10 years offshore experience before taking on something like the Claymore on your own. I was pleased he was on board.

View from the hospital on Claymore

Claymore was busy with 240 people to look out for and there was a waiting room with at least half a dozen customers to see before morning coffee break.

The gym was huge and superb and I made good use of it.

The food was also excellent. Saturday Steak night (cooked to order, for your liking) was closely followed by a Sunday roast and possibly the best apple crumble and custard in the world.

Usually by 9am my sides were hurting with laughter about one thing or another and it started to feel like home.

Many of the guys had been with Claymore longer than they had been with their wives.

The platform was friendly and day by day, I gained more and more experience and ventured further outside my comfort zone.

Life on board the Claymore. Superb hospital, training kit and gym!

Martyn was a godsend and he worked hard to bring me up to speed with how things ran on the Claymore. He was infectiously enthusiastic and I lapped it up, relishing the learning opportunities that came my way and my CV started to grow.

After just over 2 weeks, I was notified that I had been asked back by the OIM (the rig boss) to cover a full 3 week stint later that summer.

After 3 weeks off, I returned and was welcomed like an old friend.

After 2 weeks, Martyn was off to the Auk, a smaller neighbouring platform to start his HSE role. I was left on my own as the sole medic on Claymore after only 2 years offshore. Either I was doing something right or they were desperate!

I was doing full inductions on my own as well as running the huge sick bay and doing the water testing.

It was a mental week with several challenges thrown my way, but I loved it and looked forward to getting up every morning for work. It was so different to working on the ambulances.

I was sad to leave the Claymore but she had given me a huge wealth of experience and a huge confidence boost.

I asked Martyn one day, after a particularly ridiculous morning: “Does it get any bigger than this?”

Martyn laughed.

“No” he said. “If you can handle Claymore, you can handle anything”.

“You have no idea how much sh!t we are in….”

Fuzine, Croatia

Osama Gobara, fondly known as ‘Oz’ watched despairingly as his cave diving buddy Mauro ‘faffed’ in only a way that Italians can faff.

“It’ll be fine” was the reply in a slightly high-pitched, laid-back Italian accent, dismissing Osama’s worries as he threw bits of diving and caving gear in the car.

Oz, gripped with dread, knowing what it meant to be late and disorganised for any expedition of mine, tried to warn Mauro…especially as they were already a day late.

“You have no idea how much sh!t we are in!” he told Mauro. He knows me too well.

All assembled for the pre-trip final briefing

Despite over 6 months of meticulous planning on the part of the British contingent (except Mitch Parry, who apart from occasionally using a computer once a week, had also got the flight dates completely wrong…) Oz and Mauro decided that it would all come together in the last 48 hours before the expedition.

Wrong clothing, wrong gas and wrong equipment was quickly put to bed by a few sharply worded Whatsapp messages from myself and they rocked up a day late, having never met any of my team before.

This didn’t look good. I could feel undertones of doubt about my choices of extra push divers and I started to feel uneasy.

I knew Oz would pull it out of the bag but Mauro was a complete unknown to me and my team – they would both have to pull their socks up.

After all, everyone was here to carry their kit. All 25 bags of it, plus 5 scooters and 4 rebreathers…

Osama Gobara in sump 2

After the 2021 expedition where I discovered yet another sump, sump 5 and some really nice but far too short walking passage, we re-evaluated the Licanke expedition. Now in it’s 7th year, it was just no longer safe to keep ending up with one diver pushing alone so far into the system. We decided to bring in reinforcements.

Finding push divers for your expedition is hard.

First, they need to be CCR and scooter capable in a 50m deep, 7 degree sump; they need to be happy carrying their rebreathers and all their bailouts in a drysuit in dry cave; they need to be team players and be prepared to join the ‘big carry’ in and out of the cave; they need to be able to lay line well and survey, both underwater and above water; they need to be able to solve any problem either above or below water but most of all – they must not be a dickhead.

We don’t want dickheads on our expedition, especially if I’m at some stage to hand the end of my line over to them. I’ll only do that for people I like, who pull their weight and earn it.

Mauro Bordignon

Rich Walker had religiously come on every exped since 2015 at quite some personal expense and discomfort. He dislikes caving anyway, so doing it in a drysuit and rebreather really doesn’t appeal to him. By his own admission, being beyond a deep, reasonably long sump like sump 2 in Licanke, made him uneasy. His expertise is in the water; he's just not a fan of getting out. I needed someone who didn’t mind this level of exposure and was prepared to push further.

So, while Rich was happy in deep support mode, Oz and Mauro were brought in to leapfrog the exploration. The exped was now 2 weeks long with rest days factored in, as the cave was getting longer – and harder.

Once they had got their pile of half-built KISS Sidewinder rebreather bits into some sort of machine that could support life, we had a briefing. Using a combination of huge printed out survey and the laptop hooked up to the telly, it was quite comprehensive. We then had the worlds biggest whiteboard and magnets to move people and gear across the cave to finalise the plan.

Chaining large amounts of equipment over the huge boulder chamber is the most efficient way of keeping things moving.

The next morning the ‘big carry’ ensued. It was pretty slick. Scooters, rebreathers, bailout cylinders, deco bottles, bags with drums full of regulators all made their way to sump 2.

Regs were tested, rebreathers built and checked and scooters checked for batteries and damage.

Owing to several items being forgotten last time, we made use of A4 wetnotes and pens at the start of sump 2. These were for check lists to make sure no divers set off into the blue yonder minus a camera, food, tackle bags, suit gas bottle, spare oxygen etc. Once you had set off, there was no turning back. The plan to cross sump 2 has always been to go hard and fast on the scooter trigger to avoid decompression. It is a committing dive.

After a day off and some mandatory last minute faffing, the plan was for me and Osama to go straight to sump 5 and dive it. We also needed to survey the remainder of sump 4 and the dry passage between sumps 4 and 5. I had been alone the previous year so a proper survey had taken a back seat.

Osama and I set off a few minutes ahead of Rich and Mauro. I towed the spare scooter and Oz the forward pushing bailout bottles. Rich and Mauro followed on with 'safeties' staged through the sump at key points and decompression bottles for the 'home' side of sump 2.

I also took a bunch of polyprop ‘washing line’ to help protect the thin exploration line at the exits of the sumps and set about rigging this on the far side of sump 2 before the others appeared.

Everyone had made it past sump 2. The game was on.

This expedition has received generous assistance from several organisations and businesses listed below. We are grateful to our Croatian friends for their help and support over the last 7 years.

The expedition reports, funded by Mount Everest Foundation, are available to read here:

Funding and support:

Santi Drysuits, Halcyon Dive Systems, Mount Everest Foundation, Ghar Parau Foundation, Suex Scooters Warmbac

Izvor Licanke Expedition Team 2022: Mark Burkey, Louise McMahon, Luke Brock, Mitchell Parry, Richard Walker

Push divers: Christine Grosart, Osama Gobara, Mauro Bordignon.

Wild World

Osama and Mauro at sump 2. Image: Mark Burkey

I was well and truly broken after that 15 hour day. I didn’t ache so much, but mentally I was wrung out.

I asked Oz how many days off he though he’d need before going back. He gestured “two” with his fingers while inhaling a mouth full of Mauro’s incredible mushroom risotto.

That was me out. I needed at least 3 days off and even then, wondered if a trip in excess of 15 hours wearing my rebreather was something I wanted to do that week. Again.

Mauro was super fired up at this point. Having seen the carry between sumps 2 and 3, Rich had no interest in going there with his JJ.

We agreed that there also wasn’t much value in having people sitting between sumps getting cold all day and as Osama and I had already moved the push bottles forward to sump 5, there was no point in Rich and I crossing sump 2. Each time a diver passes that sump there is elevated risk. Rich’s JJ had broken in numerous ways in any case so he had carried it out the cave. I left mine in and rebuilt it, so there would always be one standby diver with a fully functioning rebreather, quick access to a drysuit and fully charged scooter ready to help beyond sump 2 in case of an emergency.

Chris and Mitch in Izvor Licanke. Image: Mark Burkey

Osama managed to flood his KISS sidewinder when he carried it to sump 2. I always carried my rebreather fully built and waterproofed but for some reason the guys decided to do it their way. Some faffing ensued and after some stolen sofnolime, the unit was back working again.

Oz and Mauro set off while Mark snapped away with his camera and Lou rounded up rather less than enthusiastic volunteers to help her complete the survey.

Lou had done an incredible job or resurveying all the dry cave between sumps 1 and 2 as we could not access the old data. This is the beauty of this expedition; everyone gets to learn lots of different caving and cave diving expedition skills in a relatively comfy environment. A short 7 degree cave dive between you and daylight being ‘comfy’…

Rich, Mitch and myself posed in various positions throughout the cave while Mark Burkey tried to take pictures he hadn’t managed to before and he came out with some stunners.

Chris and Mitch in Licanke. Image: Mark Burkey

The next job was to go back to the houses and cook for the guys when they came out. The accommodation this year was 2 houses close to each other with excellent and comfortable facilities. We had tried to get a ‘camp boss’ – someone to take care of the cooking, cleaning, shopping and general domestic duties while we faffed and fixed broken things and recuperated.

Unfortunately, she got injured and wasn’t able to make it, so we put our best cooks to work to batch cook for everybody and re-heat stuff for the divers who came out late.

Back in the cave, Oz and Mauro were making good progress to sump 5 and continued laying line in irritatingly shallow cave. It surfaced, then sumped, surfaced, then sumped again…it carried on like this, with intermittent sandy air bells until they finally crossed what was now sump 8.

Not believing there wouldn’t be another sump just around the corner, Mauro set off walking in his diving gear.

The cave got bigger as he walked down a clean washed stream way, a canyon, which got higher and echoed more as he went. He went back to Oz and they shed their diving gear and set off into new, galloping size passageway.

Screen grab of 'Wild World' beyond Sump 8.

Getting bigger all the time, they filmed with the go pro and tried to estimate the size and distance they were travelling. Soon, the canyon broke out into a huge boulder chamber. There were precariously balanced boulders the size of cars everywhere and some stalagmites close to the walls. The big breakdown chamber reminded me of a smaller version of the Salle de la Verna.

Trudging up and down the big boulders, Mauro was non-stop singing “OOOOH Baby baby it’s a wild world……doo do do dooo do do….”

Oz is deaf to him, so carried on trying to measure things mentally.

They came across another sump. Sump 9.

Neither of them had a mask or diving gear, understandably, but as with the others it was blue, clear and inviting.

Filming with the go pro as they walked back, they made their way back to sump 2 where they took a 15 minute break and a short snooze before heading back through the deep sump.

Some of the team went back into the cave to meet them and get the news. They had been underground about the same time (15 hours) plus a bit of faff at the start.

There was still a lot of work to do. All their discoveries needed to be surveyed and they wanted to do a bit more filming.

Owing to Mauro’s incessant singing, we decided to call the new, gargantuan chamber; “Wild World”.

Izvor Licanke had not done what she had promised. We were sure the cave would close down.

Instead, she opened an enormous, 30 metre high can of worms...

Survey Izvor Licanke 2023

This expedition has received generous assistance from several organisations and businesses listed below. We are grateful to our Croatian friends for their help and support over the last 7 years.

The expedition reports, funded by Mount Everest Foundation, are available to read here:

https://www.mef.org.uk/uploads/uploads/MEF_22-36_FullReport.pdf

Izvor Licanke Expedition Team 2022: Mark Burkey, Louise McMahon, Luke Brock, Mitchell Parry, Richard Walker

Push divers: Christine Grosart, Osama Gobara, Mauro Bordignon.

Funding and support:

Santi Drysuits, Halcyon Dive Systems, Mount Everest Foundation, Ghar Parau Foundation,

Manic Media

I was delighted to get a call much sooner than expected, to join my second home the DSV Boka Atlantis, for an emergency job in the North sea.

A pipeline had liberated itself from the seabed so we were off out to fix it with our hotshot team of sat divers (cue the A-Team theme tune…)

Coming home from weeks away offshore is like Christmas every time – there is always a bunch of parcels you forgot you ordered waiting for you.

One such parcel was particularly exciting for me. Owing to the charity work I do for Ghost Fishing UK and original cave exploration, which is my life’s passion, Santi Drysuits offered me an ambassadorship.

Christine in her new Santi Drysuit. Images by Marcus Blatchford at Vobster Quay

It is an honour to be asked by a top end drysuit manufacturer who truly believe in supporting our charity and supporting those volunteers not just at the sharp end but who graft so hard for no remuneration behind the scenes.

The media have been busy with our charity and the BBC Women’s Hour Power List 2020 has kept on following me and they finally persevered and caught up with me when I got home for an interview.

You can listen in here:

Not long after, BBC South West nabbed me for a piece about volunteers who look after our southern coastline.

A slightly stranger one was being asked to talk about working offshore for Woman and Home magazine. They were quite insistent that the interviewee should be 40 or older and never appeared in a similar magazine. I was quite sure that this was not my genre but sadly even more sure that I had, indeed, hit 40. This milestone was a total anti-climax and due to Covid had been spent on the oil rig, Dunlin.

You can read the full article online here: Woman and Home - Women at Sea

I didn’t tell anyone it was my birthday as it seemed pointless. I guess the party will have to wait a while.

In the run up to my first ‘live’ ghost fishing mission of the season, I jumped into our local quarry with photographer Marcus Blatchford and fellow Cave Diving Group member Connor Roe.

I hadn’t seen Connor since his efforts in Thailand assisting with the underwater rescue of the Wild Boars football team.

By the way, if you want to read all about it from the horse’s mouth, I highly recommend this read from one of the guys who found them. It’s probably the only truthful account of the whole affair you will read.

I’m proud to know both Rick and Connor, Rick much better over the years and they are the most down to earth people you could ever meet.

Connor Roe, with one of his less fortunate victims…

Photo: Christine Grosart

We had a lot of fun with scooters and cameras and I got to try out my new Paralenz Vaquita. I had a good shakedown with my DSLR wide angle underwater set up in preparation for the Brighton Ghost Fishing UK mission where I hoped to bring back some images of the action.

Underwater photography: Expensive, difficult and time consuming!

Christine in her new Santi Drysuit. Images by Marcus Blatchford at Vobster Quay

Christine in her new Santi Drysuit. Images by Marcus Blatchford at Vobster Quay

“You need to stop doing that”

Christine diving her KISS rebreather

Some of the best, if a little uncomfortable advice I was given when I was a Cave Diving Group trainee, came from none other than Rick Stanton.

As a diligent and conscientious trainee, I would spend hours poring over cave surveys before I went diving. I would work out the gas I needed, what size cylinders to take, whether there would be any decompression and the depth profiles.

It wasn’t a bad thing to be learning, but of course I was diving in caves where others had been previously and lines were in situ. They had been surveyed and, in many cases, photographed and filmed (less so in the UK, I hasten to add).

The CDG refers to these dives as ‘Tourist and Training dives’ in its newsletter, which is the bible for finding out about submerged caves not just in the UK, but around the world.

Anything where nobody had ever been before; a new discovery, was referred to as ‘Exploration’.

You can see then why it irritates genuine cave explorers to hear the latest cohort of cave divers saying they have explored this cave and that cave - and then being immediately disappointed to find they just dived a tourist route. The word is getting muddied by those who think that because it is their first dive in the cave, it counts as ‘exploration’.

The term in the cave diving world is very clear cut, to distinguish between new discoveries and ‘tourist’ dives along existing line. If you are not the first person to go there, it is not exploration.

Chris practises line laying on her KISS rebreather, using a Santi drysuit and Halcyon wing, backplate and torch.

“You need to stop doing that” Rick said, bursting my bubble. “I know you’ve been taught to study cave surveys but that won’t help you when you go into new cave”.

I was 26 years old and about to undergo my qualifying test in the CDG.

I didn’t dawn on me then that Rick was already looking at my future in being a cave explorer and I shrugged off his comments as something only he did - and carried on studying the survey in front of me.

He was right though. If nobody has ever been there, not only will there be no line in place to follow but you will have no idea of what the cave will do.

You get a hunch of course, from years of caving and cave diving experience and having dived other caves in the region.

I have an unfinished geology degree so have an inkling of what a cave might do.

But Licanke was acutely unhelpful.

Christine prepares for one of her early exploration dives, extending the end of the Garrel, France, 2012.

Caves in Croatia had a habit of plummeting super deep, 100 metres + and when we hit 50m in Licanke, we feared the worst. Decompressing in 7 degrees was miserable. Given the cave already had a dry section, we figured it would do one of two things; Go to surface, or plummet deeper.

Really, really unhelpful.

All we could really do was plan for how deep we were prepared to dive and how much deco we were prepared to do on any given dive. That would determine the limit of exploration.

I’m not in the habit of winging it and sorting it out at the the deco stop. That’s silly.

To plan for virgin exploration, we simply look at our logistics, capabilities, gas available and time available. Put simply, based on what we did last time, we make a personal decision on what we are prepared to do this time.

I was very fortunate to learn from the best. Supporting divers such as Rick Stanton, Jon Volanthen in their explorations and learning to cave dive with Clive Westlake.

It really is that simple. Conversations go along the lines of “I really don’t want to do more than 3 hours deco in there tomorrow” or “We’ve only got two bottles for pushing….so how far will that get us if the average depth is 30m, 40m or 50m?”

You need to know your swimming speed, scootering speed given the conditions, plan for various average depths and decompression contingencies.

Thermal factors need to be considered and lots of ‘what ifs’.

What if we lose a stage bottle? What if we lose a scooter? What if the rebreather malfunctions?

We try to mitigate all of the ‘what ifs’ and inevitably, the cave will throw something at us that we hadn’t bargained for. That’s exploration.

I kitted up into my KISS rebreather and performed my final checks.

Chris prepares her KISS rebreather

Rich was unable to dive, which meant several things:

- I would only be able to carry enough bailout gas* to get me home from sump 3, thus I would not be able to undertake exploration alone on this dive.

- I was also towing a back-up scooter which limited the amount of extra bailout I could take.

- I would need to carry all my equipment through the dry sections without help and this would be extremely time consuming.

- There was nobody able to rescue me if I got trapped beyond sump 2.

I set off, disappointed that this was only to be a recce dive, but I already had a wild and cunning plan in my mind to salvage the expedition - I just needed one phone call.

*Bailout gas is contained in open circuit scuba cylinders, which are used as a safety factor to get a diver home in the event or rebreather malfunction or failure. Rebreather divers should always carry enough bailout gas to get them home from the furthest and deepest point in the event of rebreather failure.

Rich packs tackle bags

Funding and support:

Santi Drysuits, Halcyon Dive Systems, Mount Everest Foundation, Ghar Parau Foundation, Suex Scooters Warmbac

Largs to Gran Canaria

Dock yard in Las Palmas. DS7, very similar to the DS4.

Whilst I've been pretty comfortable mooching around the North Sea as a medic, with the occasional excursion to Denmark, the Netherlands or the occasional hazy night in Lerwick, I haven't really been anywhere 'nice' in my offshore travels.

By nice, I mean warm - and safe.

So, I couldn't really turn down my next little job which was to travel with a drilling vessel as she made her way to the dock yard in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria.

The DS4 was infamous for going AWOL from her cold stack in Largs, in the firth of Clyde when she broke her moorings in huge gales.

The weather when I arrived was almost as vile and I was drenched before I even made it up the gangway. I was looking forward to some better weather in the canaries!

A 10 day very pleasant transit saw us arriving at a very busy port, with a handful of sister ships tied up all awaiting work.

My company had arranged a flight home for me, which they put back at my request so I could see a bit of Gran Canaria.

I wondered if there was any decent cycling here...

It turned out that the canary islands are nothing short of a cycling 'mecca'. Lacking confidence and still terrified of cycling with other people who were all absolutely guaranteed to be better than me in every single way possible, I opted to go on a 'cappuccino' tour with Freemotion Bike centre. This sounded gentle and surely must involve lots of coffee stops and photo opportunities.

If it was too easy (after all, I had been doing Alpe de Huez on the watt bike every week offshore) I could pick a harder tour on a later day.

I know nothing about bikes. They have two wheels and that is pretty much it. I'd heard that Specialized were a good brand and for 30 euros a day rental, I picked one.

I didn't have my cycling helmet with me, but one came with the rental. I had already warned FreeMotion that I would need 'normal' pedals as I couldn't yet ride cleats. No problem, they said.

After a very pleasant evening at my all inclusive hotel apartment, complete with pool and kiddies evening disco, I got a taxi to the bike centre only 20 minutes away and got in the queue to collect my helmet and bike. I hadn't brought any suitable cycling shades and figured I could just grab a cheap pair at the bike shop.

One 140 euro pair of Oakleys later and I was set to go.

It was my first time on a proper road bike and my first time on road tyres. What could possibly go wrong?

Betty, our guide, advised me to have a quick ride up and down the car park to get used to the bike. After watching me give it a spin she advised me to do it again.....

We weren't far away from setting off when I noticed lots of people looking in my direction.

Did I have a hole in my shorts? Were they admiring my trainers? Feeling self conscious and fighting off every desire to just give the bike back, get in a cab and go straight back to my hotel, I realised what they were looking at.

I googled it later and discovered to buy one new would cost about £5000.

I took out some extra insurance and sympathised with Betty, our guide, who gently pointed out that even she 'didn't get to ride that one'.

Betty spends her winters in Gran Canaria, guiding tourists around the island on two wheels. Fair enough.

She also spends her summers cycling up mountains in Switzerland.

Oh shit.

How on earth she tolerated hapless tourists like me, day in day out, I don't know. She was truly inspirational and I wanted to be like her - immediately.

There was only one other guy with our 'cappuccino' tour. A banker, quite tall and pleasant was allowed out occasionally to go cycling.

Cycling scenery Gran Canaria

They both set off at a brisk pace. I could keep up - just - but as usual, got a bit bedevilled at roundabouts (going the wrong way round now as well) but the traffic was forgiving. Confusingly so, in fact, as the traffic here gives way to cyclists on roundabouts.

To a Brit, where the traffic basically tries to kill you at every opportunity, this was most perplexing. I wobbled and almost fell off in the middle of a 4 lane backwards roundabout when the traffic slowed and politely waved me through.

I just about managed to keep up, wondering how I'd do 35 something miles in the heat, when they both instantly left me for dead each time we came to a hill.

I dropped Expensive Specialized into his lowest gear and span comfortably up each hill - getting there in the end - and enjoying the super fast, super smooth downhills on the other side with the sea breeze cooling me down and the view of the bright, sparkling azure ocean in my view the whole time.

Speed both thrills and terrifies me. I'm acutely aware of what will happen to my body if I come off at 30mph - I've done it enough times on racehorses - but it's the skin removal and traffic that makes me twitchy. But hey, I'd have been having fun until that point.

We stopped briefly on occasion to let us regroup. After setting off a few times up hill I noticed a weird buzzing sound coming from banker's bike.

He was on a bloody e-bike!!

For the love of God!

At about half way (home!) we stopped for coffee. This seems to be a thing with cyclists. Coffee and cake.

We didn't stay long enough for cake and we were off again. Once back at the bike shop I had another coffee then cycled the 8 miles back to the hotel for a dip in the (very cold) pool.

After a day off, I cycled back to Freemotion to repeat the exercise, though this time with a larger group. We set off on the Cercados Espino tour, taking in a stunning old river valley.

The rock formations were stunning and the blue sky exhilarating. It was a gentle 1% incline for several miles and the road surface was like velvet. We stopped for lunch and coffee and cold cola at a cafe just before the valley begins to get stupidly steep. I had lunch with a german cyclist - which is not something I ever thought I'd say - and we sped back down the valley in half the time, enjoying the gentle downwards incline.

Delighted that I just about managed to keep up with the group on a hot and busy hill back into town, plus managed to navigate a huge roundabout by myself when all Betty's ducklings got across together and left me stranded, I handed Expensive Specialized back in.

I was a few hundred quid lighter, but had really enjoyed cycling in the heat on superb roads, considerate traffic (I don't think I even noticed a car, other than the one who waved me across the roundabout, despite it being his right of way) and I have now found my favourite winter haunt.

Moody Mull.

Mull, Scotland

“Is anyone here a geologist?” our rather chilled out kayak leader asked.

“Me, me, meeeeeee!” I said, rather excited …and putting my hand up….seriously….

Well, not really. I did study geosciences for several years with the Open University and loved it…but never finished the degree because I had another medic degree going on….I digress.

We were on the Isle of Mull. Looking to cheer myself up after a rather stressful, fraught and astonishingly horrible start to the year, I clicked ‘going’ on a Facebook kayaking trip run by Ali Othen Mountains and paddles.

Packing boats, ready for the off.

It was 7 days kayaking, circumnavigating Mull with 6 nights wild camping. We would be completely self-sufficient, taking all our camping and cooking gear with us and I was really looking forward to seeing places only accessible by kayak and wildlife spotting.

I flew home from work, threw the kayak up onto the roof and packed the car, before the long drive up to Oban. From there I jumped on the Craignure ferry and set up camp at the pricey but very smart Craignure campsite. I had a pint and a chippy tea with Ali and my diving buddy Darren who has lived on Mull for quite some time now.

Darren’s wife is part of the Otter fancying society on Mull and they build the otter crossings around the island. They also occasionally end up with run-over otters in their freezer for autopsies...nestled in between the oven chips and on top the peas, apparently...

After a cosy night in my van we met up with the other two random paddlers who were on the trip. I think it is safe to say neither of them were my type of person, but there was nothing I could do about it. My plan was to learn how much stuff I could get into my kayak, how it would ride fully laden, what worked and what didn’t work, so I could plan my own adventures going forward.

Lunch break

We set off in glassy, stunning conditions from Craignure and paddled along the south coast, wild camping along the way. We stopped off at gorgeous, white sandy beaches but as ever, they were blighted with piles of rubbish and I spied one large green fishing net.

Mostly buried and too big to even think about taking with me, I had no choice but to leave it.

I did spy a smaller piece which looked in good enough condition to do something with. I took pictures and logged the location on my phone. We found a comfy-ish spot for the night having paddled 16 miles.

On the second day, we arrived at Fidden Farm after a 25 mile paddle, familiar to me from last year’s adventure in Scotland.

After a night here, we crossed to Iona which was my first decent open water crossing. It was lumpy but prepared me well for what was to come.

From the northern tip of Iona we headed straight for Staffa, a 13 mile open crossing, to the famous Fingal’s cave.

The crossing had a reasonable swell but was perfectly manageable – until the tourist boats came thundering past and created huge wakes. Initially terrified, I settled down and began enjoying surfing them as we made the last strides towards the cave entrance which was fortunately in good enough condition to enter.

Balancing my phone on my lap, I shot some images and video and managed to choreograph Ali into position for that classic ‘kayak in a cave’ shot. The cathedral like cave entrance, made up of volcanic basalt columns was seriously impressive.

Not keen on getting tangled up with tourists, we had a quick bite to eat then headed on another open crossing to Treshnish and stopped on Lunga.

Puffin takeover on Lunga, Treshnich, Scotland. Images: Christine Grosart

The weather started to come in and rain and wind meant I got very good at putting my tent up quickly.

In the morning the waves were still a bit necky for crossing over to Calgary bay, so I took the opportunity in the sunshine to enjoy the colony of puffins who were busy building nests in the cliff edge.

They weren’t shy at all and I was pleased that I’d taken my DSLR and 300mm lens to capture their antics. I could have spent more than a few hours in the sunshine among the primroses and bluebells watching them.

Once the weather settled a bit we made a very bum-clenching 8 mile trip around to Calgary Bay. Normally beautiful, yet again on my second ever visit, it was overcast, windy and raining.

We hunkered down in our tents and despite Ali dutifully checking the waves every few hours, they wouldn’t calm so we had to spend another night in the rain, stuck fast.

It wasn’t looking hopeful to get around the corner to Tobermory.

Stunning south Mull, Scotland

As another night passed, this time with no sleep and some weird antics going on outside my tent, I decided to call it a day. We had to head back by bus to Craignure to pick up the cars to drive the kayaks around the corner in any case. I decided that this was a good time to bail. The Sound of Mull would keep.

I was grateful to get back to my cosy van and my own company and decided to make the most of my free time and head back to the beach where I had seen the lost fishing net.

This was easier said than done.

We had arrived on the beach by kayak and with a bit of advice, google maps and a helpful dog walker, I strode off confidently in completely the wrong direction to the wrong sandy beach!

It too had plenty of lost fishing gear washed up along the shoreline, but it was the wrong rubbish and the wrong beach.

Off I set on what should have been a half an hour walk…turning into a 2 hour epic!

Scaling cliffs, dodging sheep and landing thigh deep in a bog…I finally made my way to the correct beach..which I could have easily walked to down a perfectly good track from the car had I not set off in the wrong direction…

Hey ho. The sun was out, it was absolutely stunning on that southern side of Mull and I bagged up the net while another group of paddlers took a break nearby and the sea sparkled continuously.

It was possibly one of the most beautiful views I’d ever witnessed in the UK and I enjoyed it before heading back to the campsite and then Oban for the next crazy couple of days.

Ali keeps the lost art of writing post cards alive.

"You scared the sh!t out of me!"

I made a hasty exit from the 7 degree sump, wondering why I couldn’t have chosen a different hobby…

Izvor Licanke - class of 2021.

It was an early start in the Licanke house.

Anton and I didn’t mess about getting changed and heading into the cave, arriving in plenty of time to dive sump 2.

Anton elected to follow me as he had never dived this sump and it was milky visibility. Fortunately one of my back up lights has a mind of its own and often decides to turn itself on at depth. This gave Anton a welcome ‘lighthouse’ to follow in the gloom as we crossed the sump and we soon met our scooter drop, somewhat prematurely, and swam to the surface to de-kit.

As I surfaced, the dive line felt a bit flimsy in my hand. I grabbed onto it so as not to de-rig Anton and at that moment, it snapped just above the water’s edge.

That was lucky.

I waited for Anton to get out of his gear. He could see what had happened and in silence I repaired the line and we started moving our gear through the dry cave.

After a few journeys to sump 3, we had a brief chat before setting off through the sump. It only takes 4 minutes to cross sump 3. Anton was on a mission and had got all his gear to sump 4 before I had even exited the water.

He got into sump 4 first and reached up for his bailout bottle, which was lying on a ledge just above the water. The bottle seemed to catch on something and as he pulled it towards him, it nose-dived violently straight onto a sharp flake of rock. A loud hiss and puff of gas was followed by silence.

Oh shit.

The rock had taken a chunk out of Anton’s regulator hose.

I stared at it in disbelief. This cave had bitten just about everyone in one way or another and now even Anton had not escaped its clutches.

Bugger.

Anton declared he could fix the hose back at sump 2, but could not dive any further into the cave.

It was down to me now.

As before, there was nobody who could come and get me in the event of a problem.

I got into sump 4, clipped off my line reel ready for deployment and set off. I knew that the line went about 100 metres distance, dipping to 28m depth, before it ended at about 10m. After that, who knew what it would do?

It took a while to get to the end of the well-laid line. I was taking it steady and trying to get a feel for this sump. It was much like the other sumps; sandy, undulating floor with the occasional jagged rock here and there. I found the end of line with some of it bundled neatly under a big rock. It was safe and secure, so I tied into it, feeling huge relief that finally we were getting somewhere.

The cave gradually undulated shallower and I was laying line at about 10m depth through easy going, large passage when I suddenly hit a huge, vertical wall. Looking left and right, I could see no ongoing passage - the only way was up.

Laying line up a sheer wall on a manual rebreather is tricky. I took my time, making small tie offs wherever the opportunity arose and there weren’t many of them. As I got to about 4m depth I started looking up and sure enough, there was the glistening ripples of air surface. I bobbed to the surface only to crack my helmet on a roof projection.

Arse.

Moving away slightly to the side, I was now floating in a perfectly round, turquoise pool.

Where the hell was the way on?

Just across the pool was a large flake of rock slicing across my view of the otherwise circular sump pool. That must be it.

Swimming carefully on the surface over to the rock flake, I stuck my nose around the corner.

There lay a perfect de-kitting ramp, a flat stream passage with cream, orange and black walls and a ledge which looked like a perfect de-kitting bench!

Brilliant!

I de-kitted, turned off all my bottles and wandered down the brand new stream passage. The roof was about 30 metres high, the passage was a couple of metres wide, bigger in places and the stream flowed gently towards me under my feet.

It was beautiful and for that moment, it was all mine. My own piece of planet earth that nobody else had ever seen. It had never seen light, never been walked on and I had no clue how long this would last.

As I walked down the easy going passage, stopping to have a good look up into the tall roof, I let out a “Woo Hoooooo!!” of delight. At this point, I realised I had left my Paralenz dive camera clipped off to the nose cone of my scooter in sump 2.

I didn’t actually mind at this stage and concentrated on not tripping over and hurting myself, or putting a hole in my drysuit.

It was far too soon but some 70 metres later, I came across another perfectly round pool of turquoise water.

I walked straight into it to check if it was a lake, a duck or a sump.

It was a sump.

This was the cave that kept on giving. I had found sump 5.

Izvor Licanke survey 2021

With only one bailout bottle (again) I didn’t chance it. I wouldn’t have enough gas to make any meaningful progress and bail out if I needed to.

I took a compass bearing of the passage, counted my paces back to sump 4 and kitted up to dive back to a waiting Anton.

As I surfaced, excited to tell him the news, my BOV (bailout valve) started to free-flow and we had quite a job turning it off. I lost quite a lot of diluent gas and this was a concern as I still had two sumps to dive home.

As we were sorting out the problem, I felt something strange by my right hip. I reached behind to locate my line reel and found it had unclipped itself and rolled back down the slope, underwater.

With a lack of diluent I figured it would have to stay there, it was not worth diving back into the sump to find it.

Anton and I dived back through sump 3 and embarked on the painstaking carry back and forth to sump 2. Once all our gear was safely stashed, we unpacked the mini dry tube and began a grade 5 survey of the passage between sump 2 and sump 3. This was a relaxing affair and felt like a serious achievement to finally get this done and dusted.

It was finally time to dive home. I dispatched Anton into the sump first as there wasn’t much kitting up space for two people. As I turned on my rebreather, I realised I barely had 10 bar of diluent left. This was not good. Scratching my head, I worked out a way of plumbing in my bailout bottle to my rebreather and this worked remarkably well. The partial pressure of oxygen was easy to manage and it was a surprisingly comfortable dive home.

I surfaced to a very concerned team. Mark was particularly upset.

Anton did not know that I had needed to rectify a rebreather problem and of course, this took time. When he surfaced, he told the team I was a few minutes behind. In fact, I was an hour or so behind.

I had not even started kitting up when he’d left and the team were getting more and more concerned.

Anton did not have enough battery remaining on his scooter to come back looking for me easily, so they waited and waited, getting more and more worried as time passed.

They were pleased to see me, but much like when a child runs out into the road, you greet them with a bollocking.

Lou, doing her favourite thing

It was dark when we finally surfaced from sump 1. The guys had sorted pizza for us and beer. I was almost too tired to eat it.

We had been underground for 14 hours and underwater for 124 minutes. Sump 4 had been passed, new cave discovered and sump 5 was there, just waiting to be dived.

After a day off and an evening at our favourite ‘Bear’ restaurant, we headed back into the cave to recover all the equipment. Possibly due to familiarity or maybe just motivation to get the job done, the gear all came out in half the time it took to go in.

As usual, I was bringing up the rear and did a final ‘idiot check’ beyond sump one to make su

re all items had been taken out of the cave. I kitted up into my twinset to dive home.

“Where’s my hood?”

Vaguely remembering that I had packed a hood for safe keeping in a pot - which had doubtless headed out of the cave in someone’s bag - I looked dejectedly at the Santi woollen beanie that was lying on a slab of rock.

That would have to do.

I made a hasty exit from the 7 degree sump, wondering why I couldn’t have chosen a different hobby.

From left to right: Richard Walker, Christine Grosart, Mark Burkey, Louise McMahon, Anton Van Rosmalen, front: Fred Nunn.

I cannot thank the team enough for all their hard work and support on this project, members both past and present. Also, we must thank the staff and friends from Krnica dive centre; those who arranged permits to dive the cave, loaned us cylinders and sorted our gas.

We also wish to thank various diving and caving outfits who have assisted in some way, along the way:

We must also express our gratitude to the Ghar Parau Foundation for yet again giving us a grant and likewise, the Mount Everest Foundation for again selecting our project for an award.

We also wish to thank various diving and caving outfits who have assisted in some way, along the way:

Santi Diving; Halcyon Dive Systems; Suex Scooters; Fourth Element; Little Monkey Caving; Narkedat90

Dare to Tri

“There is not enough money in the world to persuade me to do that ever again!!”

These were not the words I had hoped to hear when one of my caving clients emerged from the regular haunt, Swildons Hole cave, high up on the Mendip Hills.

Usually people are tired, but exhilarated. I was surprised that an Olympic triathlete hadn’t taken to her first time caving as I’d hoped. Physically she had no issues at all, but mentally – the underground world just wasn’t for her.

Having previously spent many years at ungodly hours of the morning, up before the sparrows to present BBC breakfast from the red sofa, Louise Minchin was used to putting on a brave face and a front – even when things were going horribly wrong.

Nothing went wrong on this trip and we had a fantastic day – but nothing would encourage her to try it again.

My exploits in caving and cave diving had inspired her to include me in her new book, due out May 2023 – called:

‘Fearless’ – Adventures with Extraordinary Women.

I had no idea how she found me – but I’m so pleased she did.

Not so much that I had featured in her book, don’t get me wrong, which was super lovely – but I had met a GB triathlete…and my mind started whirring.

Louise Minchin tries her hand at caving

Newly single and in need of finding my real self again, plus my never-ending battle to be smaller, lighter and faster, I started to consider the idea that I might be able to do a triathlon.

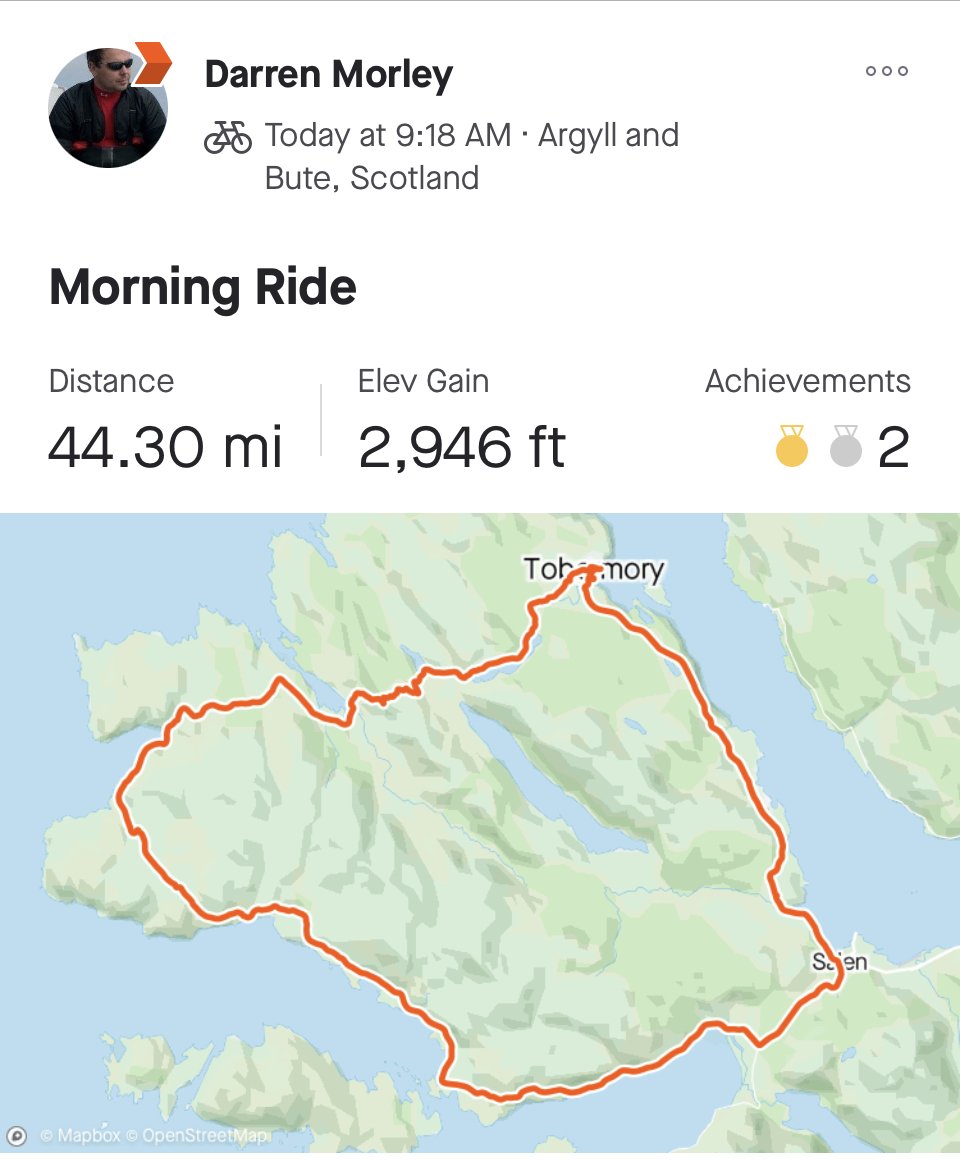

I had always wanted to – after all, as my good friend and iron man veteran Darren Morley says;

“Why be shit at one sport when you can be shit at three?!”

Christine taking part in her first ever triathlon - and loved it!

The only thing that always held me back was the inability to ride a bike.

Over the last 18 months I had somewhat fixed that – so I had no more excuses really.

Then I read Louise's book; 'Dare to Tri' and I was hooked. I just had to do this!

Langport Triathlon 2022

Another friend suggested the Langport triathlon. A friendly, local event, the super sprint looked perfectly doable. Only 200m swim, 15km bike ride and a 3km run. How hard could it be?

Christine in her first triathlon

"Did you see them?"

Winners of the 2022 Fishing News Awards

The drive from Oban to Peterhead is a pain. Let me explain.

I’m a trustee of the charity Ghost Fishing UK and we were surprised and delighted to have been nominated for the Fishing News Awards in Aberdeen that week.

Not one to turn down a posh party, I booked the time off work and had a few days spare in Scotland beforehand.

Seizing the opportunity, I booked my VHF short range radio exam in Peterhead sailing academy while I was in the area. It had been a long time coming as the exam centres were slow to re-open after covid.

With that passed and out of the way, I found myself in Peterhead at a loose end. Peterhead is one the most significant fishing ports in Scotland, if not the UK, so I thought I’d go and do a bit of ‘fisheries liaison’ for the charity, after I took on the role among other roles, last year.

After a brief visit to Peterhead, in the pouring rain, I decided to make the most if this rare free time in Scotland and head on up to Fraserburgh.

This port had been super supportive of our charity and I was met by Tommy the harbourmaster and Jill Smith, who took an awful lot of time out to talk to me, answer my questions and understand more about the charity.

It was during this conversation that Tommy said “We’ll see you at the Fishing News Awards then on Thursday!” We would indeed.

“And the expo at the weekend….”

Pardon what?

“The expo. You are going aren’t you?

It is THE fishing event of the year. You HAVE to be there!”

I hung my head in shame. I had no idea what the Scottish Skipper Expo was or had even heard of it. It began the day after the Fishing News Awards and all our expo stand stuff was in Cornwall with Fred Nunn.

I promised I’d buy a ticket and go as a delegate, to at least start some conversations.

The rain continued to pour and I went back to my car and phoned Fred to tell him about my successful meeting with the harbour. I also told him about the expo.

“Well, I was going to come up to the awards anyway…” said Fred (news to me) “So I could chuck all the expo stuff in the van….if you can get a stand?”

A few manic phone calls later and we had a stand secured. We were going!

A chilled posh frock evening had turned into a frantic 3 day event.

Christine

Dolly our social media lady was on her way up by plane. We stuffed her into a taxi so Fred and I could spend the day setting up the stand at the P&J live exhibition centre, a seriously impressive venue next to Aberdeen airport.

Then it was poshing up time. Most of us had forgotten to scrub up after 2 years of covid and ‘not going out’.

We were piped in by some bagpipes and there was no shortage of fizz, with a truly electric atmosphere.

The food was exquisite and all locally sourced. We were joined by a gaggle of Ghost Fishing UK divers who came to represent the charity and before long, the winners were announced by the hilariously funny Des Clarke.

I’d had far too much champagne and prosecco, convinced that a nomination was as far as we would go. So both to my delight and horror, Ghost Fishing UK was announced as the winner of the Sustainability Award.

The walk to the stage was far longer that it should have been and we posed briefly for photos (thank goodness there was no need for a speech!) and ran back to my table as fast as possible, treading on some poor guy in my heels as I went….

Gobsmacked, all eyes were now on us for the next two days at the Skipper expo. Our award was in pride of place on our stand. Loads of people we had never met came to congratulate us and it was a huge ice breaker, enabling them to come and chat to us.

We didn’t meet an ounce of negativity from the fishing community and over the two days, Fred and I had all the conversations, in person, with all the people we had wanted to meet over the last several years.

Another social evening of superb food and drink had been laid on for the exhibitors on the Friday and the Saturday was a slightly quieter day at the expo, allowing us to meet and talk to key people and organisations properly.

It is so important for our charity to engage with the fishing community in a positive way and this event has shown that the fishing community care very much about the environment they live and work in and want it to thrive.

Amazing Annecy

“The Marmots were singing, the vultures circling and I froze my a** off!”

“The Marmots were singing, the vultures circling and I froze my a** off!”

Sometime in the early 2000s, en route back from the epic Dent de Crolles cave system in the Chartreuse, France, we swung by a town called Annecy.

Lovers bridge, Annecy, France

It frankly, took my breath away. A clean, cosmopolitan town with tree lined streets casting gentle shade over the many restaurants and bars, over looking a warm, mountain lake with a mountainous back drop. The canopies of parapentistes circled the mountain slopes, dormant ski lifts awaited winter and water skiers zoomed about all over the lake, dodging pedalos with beer swilling tourists.

It was idyllic and I vowed to go back.

It was almost 20 years before I did.

With a triathlon looming, what better excuse than to train for it on the banks of the stunning lake Annecy.

I was delighted to join a new vessel and a new company after the Licanke expedition. The Seven Atlantic is well known as one of the best flagship saturation diving vessels in the north sea. She didn’t disappoint. A friendly crew and lovely working environment, with a great back-to-back – I was able to settle into my training without issue.

I couldn’t find anyone who wanted to come with me to France at short notice. The upside was, it left me free to do whatever I wanted, whenever I wanted.

I loaded my van with a sea kayak, bikes, swimming gear, camping gear and pretty much anything I thought I might need. It was weird going to France without any diving kit.

Figuring as a free agent, time was my own, I saw no reason to bomb it straight down to Annecy. Besides, camp sites have weird opening and closing hours there so it made sense to arrive in daylight and not be trashed when I got there.

I was super motivated – captivated even – by the Tour de France Femmes. It had been some 30 something years since it had been allowed to take place. One of the stages passed through the champagne region of France. A quick search on Komoot and a few emails to the Epernay campsite and my plan was forming.

I set up shop at the campsite after an uneventful journey and planned my ride for the next day.

The route was 45 miles or so and took in all the famous vineyards such as Bollinger and Moet & Chandon.

It was warm, sunny and there were a few tell-tale signs of the tour that had passed through a couple of months earlier. I was super grateful for the municipal water fountain which also doubled as a book swap library!

The route was somewhat lacking in cafes, so by the time I got back to the campsite on just an energy bar or two, I was ready for a good feed.

On the advice of the campsite owner I was directed away from the pizza and frites I had been longing for and instead ended up in the best rated restaurant in Epernay. It didn’t disappoint I have to say.

I got on the road the next day down to Annecy and checked in at the campsite. The sky was a little moody and being September, the weather had started to become a little unstable.

Warm, sunny days were met with windy, thundery nights, sometimes with some serious mountain lightening storms.

It was during one of these evenings when the temperature dropped and the wind began to pick up, my fellow campers and I treated ourselves to the local burger van.

As I tucked in beside my awning, a lovely Welsh couple sheepishly wandered over to me. Looking up as they approached, they said "Um, I don't suppose you've heard?" They looked sombre.

"Oh" I said "Has she, ummm....."

They nodded.

The Queen had passed away. The mood on the campsite was strange. It was peaceful, people of all nationalities stopping to chat to each other - and several of us cracked open a bottle of something fizzy that we were keeping aside for some occasion.

We raised a toast.

RIP M'am.

Each day I got out to have a mini adventure. First I managed to ascend my first mountain on a road bike – the mini Col de Leschaux. Biting off more than I could chew, I went for Le Semnoz at the end of the trip which wasn’t the smartest idea. The Marmots were singing, the vultures circling and I froze my a** off! Even less smart was not taking a jacket as it’s really quite cold at the top of mountains! I was glad to get back down to the col and into the warm sunshine again.

My sea kayak gave me lots of fun on the lake and I paddled right into Annecy itself which was a stunning experience.

I found the most perfect little boat stand which made a great bike rack for practising transitions and I had a little circuit set up – swim in the lake, jog along the pontoon – transition to bike, lap of the campsite then transition to running shoes….jog round the campsite….

Unfortunately the worry of leaving the bike unattended prevented me from doing the full distance, but it was great for practising transitions.

Not long after I drove home I had the small matter of the Great Exmoor ride, which was a complete blood bath – ok, I finished it but doing such a hilly route when I was still sore after my escapade up Le Semnoz, was a daft idea.

A week later came my first triathlon.

I was delighted to complete it and not finish last. My swim was quick, but I’d over done it and was out of breath for quite a while once I’d jumped on the bike….then, given I had done no running training at all, the 3km time was very, very poor.

I knew what I had to do to improve and vowed to take myself away on another training camp before the next one.

It was fantastic to have three amazing friends turn up – complete with cream tea and prosecco and their cameras – I was so grateful to Lisa, Jo and Paul for coming along and offering support and encouragement. They are the best.

"It sounds crazy enough to be fun"

Sump 2 in Izvor Licanke is committing.

We worked out that if you go as fast as possible in the milky visibility on the scooter, you can just about pass it without having to undertake any decompression.

I scootered alone through the sump, my brain completely focussed on the thin, white line and keeping the speed up on the trigger and enough oxygen coming through my breathing loop.

Close to the end of the sump, as it started to ascend, I dropped off the scooters and made my way up the wall from 45m to the surface.

Surfacing in dry passage without somebody to chat too is both disappointing, but also relaxing.

The time is your own and you don’t have anyone else’s problems to concern yourself with.

I was impressed with the cave passage and made 3 journeys with my fins and suit bottle, then my rebreather, then my bailout bottle.

Hauling cylinders. Image: Mark Burkey

We renamed this piece of passage 'Helen's Highway' after our good friend and CDG treasurer of over a decade.

It was befitting of the whole team rather than one individual. After a cave diving and technical diving career of over 20 years, diving all over the world, to the shock of everybody, Helen took her own life at the start of the first Covid-19 lockdown in 2020.

Helen was one of those women I looked up to, wished I could be like and her generous, kind and very thoughtful nature was something I aspired to.

She once told me (when she sent me a Christmas present and I hadn't sent her one) "You don't give to receive". That was Helen all over. She didn't deserve to die that way.

It took me 20 minutes to get to sump 3 while carrying equipment and 15 minutes to go back to sump 2 empty handed.

I took it steady as I was wearing a drysuit and didn’t want to puncture it, but also moved methodically and efficiently. Being a caver of 26 years definitely has its advantages. You cannot be stumbling or uncoordinated beyond a sump.

I quite often chat to myself when I’m alone in a cave. Usually coming out with swear words and exclamations of incredulity when encountering something that is a nuisance.

Not far from where sump 2 surfaces, is an annoying boulder choke. Huge rocks balanced precariously and haphazardly atop one another block the passage. There is a convenient hole just the right size for me and a KISS rebreather to get through. I tried not to look too closely at the boulders - and tried even harder not to brush against the ones above me.

I trudged back and forth to a gravel ‘beach’ believing that the lake ahead was the start of sump 3.

Once all my gear was there, I started looking for the dive line. As I got down to water level, I realised this was not a sump at all, but in fact another lake.

Marvellous.

More swear words came out loud.

I moved my gear again, item at a time across the lake which was out of my depth and finally after a bit of rock-hopping, spied sump 3 and the line tied off properly above the waterline and well back on dry land. My ex-trainee had done good.

It was a comfortable kitting up spot and I was soon in the sump which only took 4 minutes to cross. I surfaced at the edge of a sloping ramp which led around a corner. I couldn’t see any further into the cave from the water, due to a huge rock flake obscuring my view. I knew that sump 4 was only a couple of metres further on and, given I did not have enough bailout with me to dive it, figured getting de-kitted was pointless.

Feeling a bit deflated, I set off home.

As I prepared to dive back through sump 2, I tested my 'go to' bailout bottle. This one stays with me at all times and the regulator is necklaced for easy access. I took a breath and got a complete mouthful of water. I checked the mouthpiece but it seemed intact.

Looking closer to try and decipher the problem, to my horror, the actual second stage body of the regulator itself had split. Clearly this regulator could not withstand a bit of caving.

This was completely unfixable. I was faced with diving home with only one bailout bottle and with no buddy, could not steal anyone else's.

I did not hang about on the way home and took a big sigh of relief when I reached the slightly shallower part of the cave, as I knew one bailout bottle would now get me at least to the decompression cylinders staged at the bottom of the shaft.

This trip was not one to be done solo and I vowed not to do it alone again. There were too many eggs in just one basket.

I surfaced to find a very chilly Mark and Lou waiting to greet me. They got me out of my equipment quickly and after some warm water with nothing else in it, we bagged up some items that needed to be taken out and plodded out of the cave.

Once I had something of a phone signal, I called my friend and cave diving buddy, Anton Van Rosmalen. The Dutchman was in the south of France and was wrapping up his own cave diving project in a super deep system called Coudouliére. This neighboured a system I and my team had been exploring and they were currently only 25 vertical metres away from each other…

Anton borrows Pedro Ballordi’s nail polish…

Anton had visited Licanke briefly in 2015 and not returned. This was his opportunity to see the entire cave for himself and do some exploration here.

He took an hour to think about it and line some things up, before he replied to say he was in.

He laughed down the phone “It sounds crazy enough to be fun!”

He had no idea…..

The good news for Anton was that, despite driving 14 hours to Fuzine and arriving in something of a ‘space cadet’ state, he had very little work to do. Ok, apart from completely rebuilding his rebreather and charging everything he owned, the good news was that all the scooters and bailout bottles were already in the cave.

All he had to do was dive... and cave... wearing his rebreather…

Luckily Anton dives the same unit as me, a manual KISS. He hadn’t arrived long when I was already eyeing him up as a spare part dispenser.

“I don’t suppose you’ve got a spare BOV have you?” I pondered.

“Of course”.

I knew he would have.

The front of mine had fallen off somewhere in the cave and I was worried about gravel ingress jamming it open. I put the spare in a pot ready to go into the cave.

We assisted Anton on getting his rebreather to sump 2 and did some housekeeping.

I re-lined and re-surveyed sump one and Fred, Lou and Mark set about finishing the dry cave survey between sumps 1 and 2 as the original data had been long lost. They did some bolting and photography and generally wrapped up the list of 'jobs' this project produces.

Rich continued convalescing and Anton headed back to the house to finish preparations.

The team decided to take an extra day off, knowing that the push dive would take a very long time. And it did...

This expedition has received generous assistance from several organisations and businesses listed below. We are grateful to our Croatian friends for their help and support over the last 6 years.

The expedition reports, funded by Mount Everest Foundation, are available to read here:

Funding and support:

Santi Drysuits, Halcyon Dive Systems, Mount Everest Foundation, Ghar Parau Foundation, Suex Scooters Warmbac

"We had all become distracted by the loss of a 5 grand scooter..."

Rich and I conducted the important but tiresome task of sorting cylinders to be filled, checking regulators, fixing regulators, dealing with fizzing pressure gauges and cracked o-rings and analysing each cylinder, before packing them into their own tackle bags for transportation through the cave.

This is all done in a relatively pleasant environment of Krnica dive centre and a dip in the sea afterwards is always welcome.

The team began to arrive at the airport and we loaded the rental van with Js of oxygen, trimix and air banks and Mark’s entire collection (almost) of camera gear.

We headed up to Fuzine and moved in.

Dry chamber between sumps 1 and 2. Image: Mark Burkey

The next morning we headed to the cave entrance. We had never been here in August and were shocked to see the water levels had dropped dramatically. Sump 1 was still a sump, but it added extra faff having to lower equipment down onto dry land rather than the convenient deep pool we had been used to.

Furthermore, inside the cave the normally flooded deep lakes which we scootered equipment across were now wading depth. This meant a prolonged carry with each of the 15+ bags, scooters, rebreathers and camera gear.

Another factor was that the low water levels exposed rocks that had never been trodden on, as they were usually underwater.

We weren’t long into the carry when Mark found one; carrying a heavy dry tube, he trod on a slab which I normally caught my knee on when scootering across the lake - and it snapped right under him.

I heard shouting and hurried back to the spot where Mark had ended up. His knee had shot down a slot after the rock had broken and twisted. After a quick assessment (good job I’m a Paramedic) I was happy to move him and after the initial shock, he felt better and had a good range of movement. His thick neoprene wetsuit had supported him enough to prevent any further damage and he wanted to carry on.

It was a stark reminder that we were thin on the ground for support and we couldn’t afford to lose a single person. Added to the extra time and effort involved with lower water levels, we knew this trip was going to be tough.

The carry was also interrupted by my nagging concern that I had only seen 2 scooters carried into the cave. I knew there were 3...

After some discussion, 2 divers were sent back to sump 1 to look for the missing Suex XK1. Somehow it had come free and was hiding in an alcove on the wrong side of sump 1.

Several hours later, as I headed back to the lakes to get another cylinder bag, I heard an almighty bang and loud voices. Then silence. Back at the climb, nobody was there so whatever it had been could not have been that bad….